|

28 July 2022 — Getting Letters to Sailors at Sea

Today we are spoiled in the ways we can communicate—phone call, email, text, fax, social media. We can send news in an instant, or find out how our friends or loved ones are doing. It's easy to forget how just recently it was expensive and inconvenient—or downright impossible—to share personal news rapidly over long distances.

Even when telegraphs, railroads, and then telephones began to change that for Americans at home, sailors remained hard to reach. Prior to WWII, mail to and from US Navy personnel was handled by civilian post offices. If a ship was near the port where it spent the most time, mail delivery was easy. The post office would deliver mail to an office on the dock, which would see that it found its way to the ship. Mail from sailors could be handed over to the post office. But the farther a ship got from port, the more complicated the arrangements became. Mail would have to be forwarded to ports where the ship would call, and the ship’s movements were communicated to its home port postmaster to ensure mail got forwarded to the right place.

|  | US Navy V-mail processing centers handled mail for the Armed Guard, merchant marine, and US Coast Guard, as well as some of the processing for the Marine Corps. Photo: NARA via Wikimedia Commons. | |

|

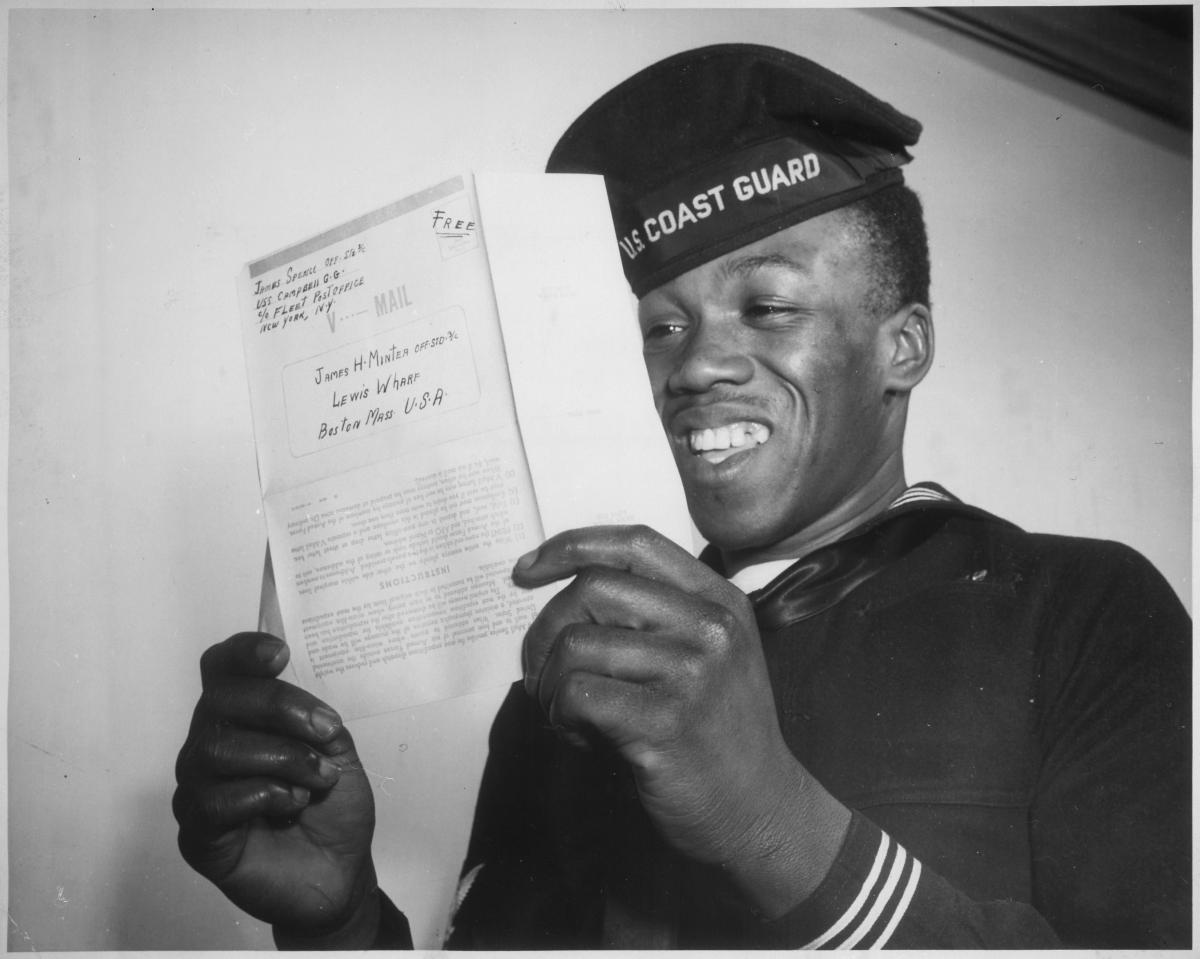

The onset of WWII, with the need for secrecy regarding ship movements, moved the Navy to establish naval post offices for the distribution of mail, so that the movement and locations of its vessels and foreign stations only needed to be shared within the internal post office. The first two fleet post offices (FPOs) were opened in 1942, in New York and San Francisco. FPOs also handled mail for the Armed Guard, merchant marine, and Coast Guard. The Marine Corps mail was dispatched by the Navy but otherwise handled by a separate section. Personal mail was recognized as an important part of the war effort; the 1942 Annual Report to the Postmaster General reported: “The Post Office, War and Navy departments realize fully that frequent and rapid communication with parents, associates and other loved ones strengthens fortitude, enlivens patriotism, makes loneliness endurable and inspires to even greater devotion the men and women who are carrying on our fight far from home and from friends.” But transporting all of that mail burned up resources that could be put to other uses. Inspired by Great Britain’s use of microphotography, the Aerograph system, the United States developed V-mail (short for "Victory Mail"), contracting with Kodak in 1942 for microfilming services. By June of that year, V-mail was up and running.

| |

V-mail formatted sheets had spaces designated for the sender, the recipient's address, and the personal message. V-mail forms that weren't filled out correctly had to be omitted from the scanning process and sent with the rest of the bulky mail. The V-mail program's biggest nemesis was lipstick, the "scarlet scourge." Letters that came "sealed with a kiss" often got lipstick on the delicate scanning machinery, gumming up the works. Photo: Nathan Beach via Wikimedia Commons. | |

|

The idea behind V-mail was simple: correspondents started with a standardized form, with designated spaces for the sender’s name and address, the recipient’s name and address, and the content of the letter, which could be either typed or handwritten with a dark pen or pencil. Those forms were sent through Kodak’s Recordak machines, which created reels of microfilm with one letter per frame of film—a single 100-foot roll could carry around 1,600 letters. Those reels, taking up dramatically less space than the paper originals, were then shipped overseas to be printed out as paper letters, to be stuffed in envelopes and mailed to the recipients. The actual process was an impressive feat of logistics, as this film demonstrates. In the period between June 1942 and November 1945, when the program was terminated, V-mail processed over 1 billion items. In the postwar era, with a much smaller fleet and less intense competition for resources, it was possible to return to delivering handwritten (and often perfumed and lipstick-marked) original letters. Increasingly, these were carried most of the way to their destination by airplane, greatly reducing the time sailors had to wait to exchange letters with home.

| |

Even today, processing the mail for the US Navy is a huge job. Here, sailors aboard aircraft carrier USS Dwight D. Eisenhower sort 32,000 pounds of mail during a replenishment at sea. Photo: US Navy. | |

|

Today’s mail traffic of course carries fewer letters and more packages, thanks to electronic communication. But for those physical deliveries, the march of progress continues. The Royal Navy began testing the concept of mail delivery by drone, and the US Navy is trying out drones for equipment drop-offs. Can regular drone mail delivery be far behind?

Sea History Today is written by Shelley Reid, NMHS senior staff writer. Past issues can be read online by clicking here.

| | | | |