|

|

Paris: A City of Ideas

Newsletter of

theparisproject.net

October 2023

| |

Who is a Parisian?

How Do We Define Natives and Immigrants?

| |

|

Faces of Paris

The faces of Paris today are immensely varied, as the city becomes increasingly international. But who is a Parisian, or when does a recent arrival become one?

In America, we call ourselves a "nation of immigrants" (while reinforcing border fences). In New York, we joke that you're a native as soon as you step off the plane and learn to say "fuggetaboutit!" But that's not the case in Paris.

An estimated 20 percent of Parisian residents are born in another country or have a parent who was. Walking through neighborhoods, one sees people who are unmistakably Parisian--and many others who reflect the tapestry of cultures that flourish there.

Here is a visual sampler.

| |  |

| |

Who is an Immigrant?

Humans, like all creatures on this great green planet, migrate to follow the food. Today, human migrations are fueled by various forces: climate change, religious intolerance, drug cartels, ethnic cleansing and political instability.

In recent history, we have come to label anyone who moves across political borders an "immigrant." The development of Paris has been all about immigrants--their influence on culture and the urban landscape, as well as their degree of acceptance, assimilation or marginality in French society.

"Immigrants" from Provinces

In the 19th century, waves of immigrants arrived from Germany, Russia and elsewhere, but the ‘immigrant” to Paris was most likely from another region of France. This "immigrant from the provinces" might as well have been foreign. New arrivals from Languedoc or Normandy hardly spoke a language in common with Parisians.

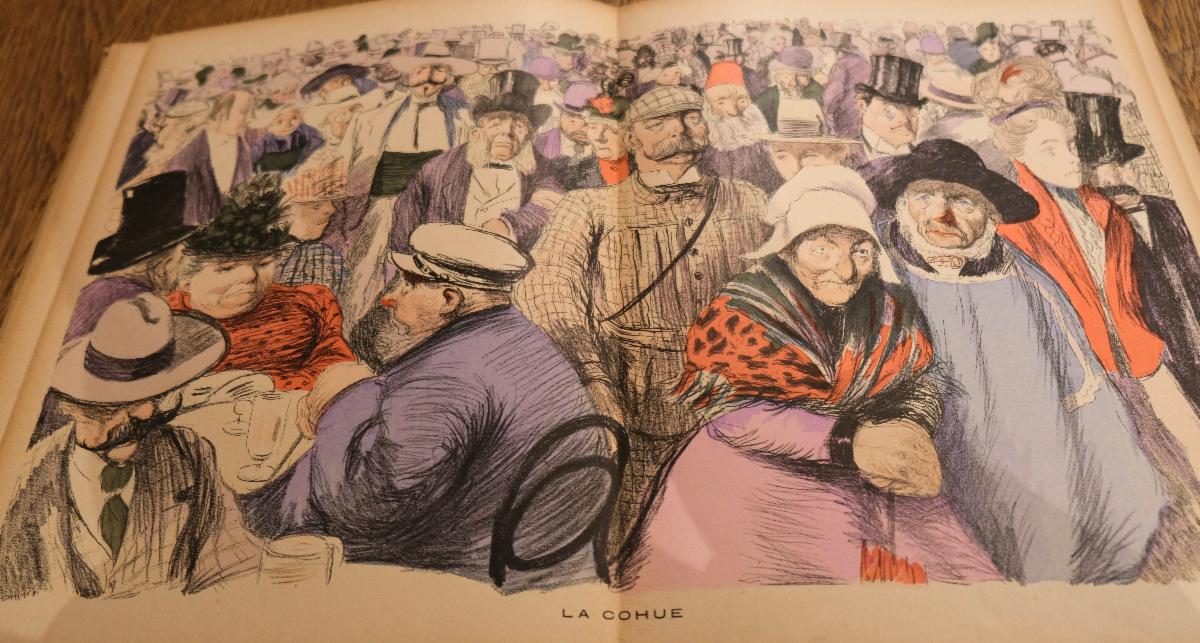

Nor did they dress in the same manner. The depiction below, from "Toute la Province à Paris" (1899) by Charles Huard, shows a "l'arrivée à Paris" or a recently arrived country rube, oblivious to derision from sophisticated city folk.

|  | |

Measuring Immigration

The French Constitution forbids the gathering of information on religion or ethnicity. All residents are, first and foremost, French.

| |

France's National Institute of Statistics (INSEE). which conducts the national census, does ask if one is born in another country or if one's parents are born outside France. It says that 7 million residents (10 percent of France's population) are foreign born. Forty percent live in the Greater Paris area, which has 13 million residents. Within Paris, 20 percent are immigrants.

Recent years have seen major influxes of immigrants from Spain, Portugal and Italy. The largest influx now is from Africa. Within that group, Maghrebis (Berbers) form the largest segment.

| | |

|

Immigrants in French Literature

Albert Camus (1913-1960) was a quintessential French writer, identified with existentialism and absurdism, yet he was born in the French colony of Algeria and came to Paris as a young man. Was he regarded as an immigrant?

|  | |

That’s complicated. Camus was the son of pieds-noirs or Algerian-born people of French or European ancestry. His father was killed in World War I, fighting for the French Army. His mother was French with Spanish ancestry.

Camus grew up poor in Algiers, where he attended university and immersed himself in leftist politics before moving to France in 1940. During World War II, he returned to Algeria and taught school. He went back to Paris in 1943 and joined the Resistance. After the war, he supported European Integration which led to the European Union.

Life in Algeria, where three generations of the Camus family had lived, fueled much of Camus’ writing: The central event of "L’Etranger" ("The Stranger"), the murder of an Arab by an emotionally detached pieds-noir, takes place on an Algerian beach. Camus’ last work, unfinished at the time of the accident that claimed his life at 46, was “Le Premier Homme" ("The First Man"). It is based on his childhood in Algeria.

Camus witnessed Algeria's War of Independence, which began in 1954, but he never lived to see Algeria's independence from France, which came in 1962.

|  | Camus was greatly influenced by the writings of Simone Weil (1909-1943). In contrast to Camus, she was a native Parisian who was forced to immigrate to London during the war. There, she aided the Resistance led by de Gaulle. One of Weil's most influential books is “The Need for Roots,” in which she outlines a kind of spiritual future for a post-war France and Europe. |  | |

Expatriates: Immigrants?

The colorful expatriates who famously populated Paris between the World Wars, comprise a kind of subtext: cultural immigrants. Some came to stay (Gertrude Stein).while others were there on assignment or a publisher's advance (Hemingway, Fitzgerald), or lived on a shoestring and a dream (Henry Miller, above).

Miller writes in "Tropic of Cancer": "I have no money, no resources, no hopes. I am the happiest man alive."

Hardly were the ex-pats immigrants, per se. But they were influential in defining the lure of Paris for emerging artists. Their indulgence of flowing wine, loose morals and cheap digs was emulated by herds of Americans backpacking through Europe in the '60s and '70s.

Romantics & Symbolists

In earlier times, poets and artists flocked from the countryside: Flaubert from Normandy, Cézanne from Provence, Rimbaud from Charleville. Were they immigrants to the city? No matter, they found their inspiration (as well as social or legal entanglements) and moved on, having left their mark.

|  | |

Sometimes literally. "Rimbaud's Wall" is a well visited Parisian landmark (above), located near St. Sulpice (6th Ar.). But was Rimbaud an immigrant to Paris? He spent only about a year in Paris, wandering the streets that inspired Baudelaire, whom he called "the first visionary, king of poets, a real God."

Despite Rimbaud's brief tenure as a Parisian, his verse continues to lure young poets to follow his steps. Patti Smith begins her book "Devotion" at St. Germain des Prés, near "the Hôtel des Etrangers where Rimbaud and Verlaine presided over the Circle Zutique." Walking the quartier, she adds: "These streets are a poem waiting to be hatched."

Consider Rimbaud, then, a cultural immigrant and spiritual Parisian.

| |  |

Immigrants Built the New Paris of the Second Empire | |

The Renovation of Paris (1852-1870) was largely accomplished with picks and shovels wielded by "immigrant" laborers from the provinces. They removed worker housing and cleared the way for new housing that provided them no benefit. The new "Haussmann boulevards" were lined with luxury housing for the rising bourgeoisie. Immigrant workers were relegated to live at the city's perimeter and exterior.

A prime example of the decimation of worker housing was on Ile de la Cité (below). The island was transformed from residential to administrative (courts, jail, police, churches).

|  | |

The renovation process relieved density in the urban center and improved living conditions for those prosperous enough to live there.

In 1860, Paris annexed much of its perimeter. The city added nine arrondissements, bringing the total to 20 (with 80 quartiers within them).This increased the city's population and tax base. The outer neighborhoods, some of them shantytowns, were developed for workers and immigrants.

The city that had been vertically diverse (bourgeois on lower floors, workers and poor on upper floors) became increasingly divided geographically into haves and have-nots.

| An abundance of immigrant labor was absorbed into the building trades, light manufacturing and retail, as well as into domestic work, which usually offered housing in the upper floors and garrets of new apartment buildings. | Correspondingly, population and density greatly increased in immigrant neighborhoods of Belleville and Menilmontant. Economic divisions have blurred somewhat as the city has become a more expensive place to live, but the outer arrondissements retain a working-class feel today. | |

Immigrants and Banlieues

Today, 80 percent of the Metro Paris population of 13 million lives outside the city. While many suburbs and outer towns retain a storybook French look, their train platforms are crowded with people of color, often dressed as in countries of origin. There also are immigrant shantytowns, such as the one below, south of Paris.

| |

High concentrations of African immigrants, many of them Muslim, live outside the city in what are sometimes called "religious ghettos."

In recent years, these immigrant banlieues have been spotlighted by police actions that some consider anti-Muslim. Also, enforcements of clothing restrictions in schools call into question the viability of laïcité or secularity, under which "Frenchness" comes before the expression of ethnicity or religion in the public arena.

France also has an unknown number of clandestine immigrants, called "sans papiers" or "without papers."

| | |

“March for Equality” Commemorated | |

The 40th anniversary of the 1983 “March for Equality,” a landmark protest of discrimination against immigrants, especially Muslims, was marked this month.

Forty years ago, eight children and nine adults marched from Marseille to Paris, where they were greeted by a crowd of 100,000 that included President Mitterand.

The current iteration of the event is “March for Equality and Against Racism.” Speaking at the event was Marseille's mayor Benoit Payan: “The Republic cannot, can no longer, must no longer allow the breeding ground of racism, anti-Semitism, hatred of Muslims and discrimination to flourish.”

____________________

Polls: Immigrants Too Numerous but Contributors

Two-thirds of France's populace believes that the country has too many immigrants, according to a 2022 poll reported in Le Monde.

|  | A more measured portrait of French attitudes is provided by another 2022 poll, this by the National Consultative Commission on Human Rights. Some 72 percent say that presence of immigrants is a "source of cultural enrichment," and 81 percent believe immigrant workers "should be made at home in France because they contribute to the economy." | |

|

Museum of Immigration

The Musée de l'histoire de l'Immigration can be visited at the Palais de la Porte Dorée (12Ar.). Current exhibitions show Asian migrations to Paris, as well as a look at the bizarre 1931 Exhibition of Colonization that was boycotted by André Breton and other writers and artists. A century ago, museums of colonies were popular in London. Amsterdam and other European capitals.

| |

|

"Our History is Yours"

Paris promotes the inclusion of ethnicities, non-traditional gender identities and other marginalized groups as part of the history and culture of France. A photographic series "Nos Visage, Nos histories" (Our Faces, Our Stories) see above) highlights the diversity of the city.

| |

Intercultural Cities

Paris also participates in the Council of Europe's

"Intercultural Cities" program. This includes promoting opportunities for Immigrants and refugees through sustainable businesses.

| |

|

Recently posted on You Tube:

"Myths and Mysteries of the Bastille," a history of the famous prison and symbol of justice over tyranny, presented in association with the Alliance Française.

"Paris a City of Ideas," an exploration of the social and ideological signs and symbols of the Paris landscape.

Watch for upcoming Zoom presentations.

Free Paris Newsletter

To keep up on events in Paris (and to refresh your French language skills), subscribe to À Paris, a monthly newsletter of events and history from the City of Paris.

| | | | |