e-Newsletter | March 29, 2024 | |

Mink, Mayhem, and Family Secrets... | |

|

Let me just say first that I love all animals, with the possible exception of certain insects. But two weeks ago, a particularly enterprising mink, yes, like the coats, brought great sorrow to the Poore Farm and inadvertently uncovered a family secret.

Read the title story following event announcements!

Credit: Newburyport Public Library Archival Center Bill Lane Photograph Collection

| |

Using Your DNA Test for Genealogy

Wednesday, April 3 and Wednesday, April 10 2024, Noon - 1:00 PM

| |

|

Splendor in the Grass: Art Inspired by the Great Marsh

Thursday, April 18, 2024, 7:00 PM

| |

|

Thursday, May 16, 2024, 6:30 PM

| |

|

Saturday, June 8 and Sunday June 9, 2024 10:00 AM - 4:00 PM

| |

Mink, Mayhem, and Family Secrets...

...by Bethany Groff Dorau

| |

Juvenile mink, photographed in the author's chicken coop in West Newbury, March 2024 | |

|

Let me just say first that I love all animals, with the possible exception of certain insects. But two weeks ago, a particularly enterprising mink, yes, like the coats, brought great sorrow to the Poore Farm and inadvertently uncovered a family secret.

First of all, a little bit of history...because I can't help myself.

Mink has always been considered one of the most luxurious pelts with which to adorn oneself, but in the 1930's, its popularity began to skyrocket, thanks in part to the growth of mink farms. With a captive population of these sleek creatures, mink was no longer just for collars and stoles. One could now spend a small fortune to be draped in a coat made entirely of mink and be the envy of the neighborhood.

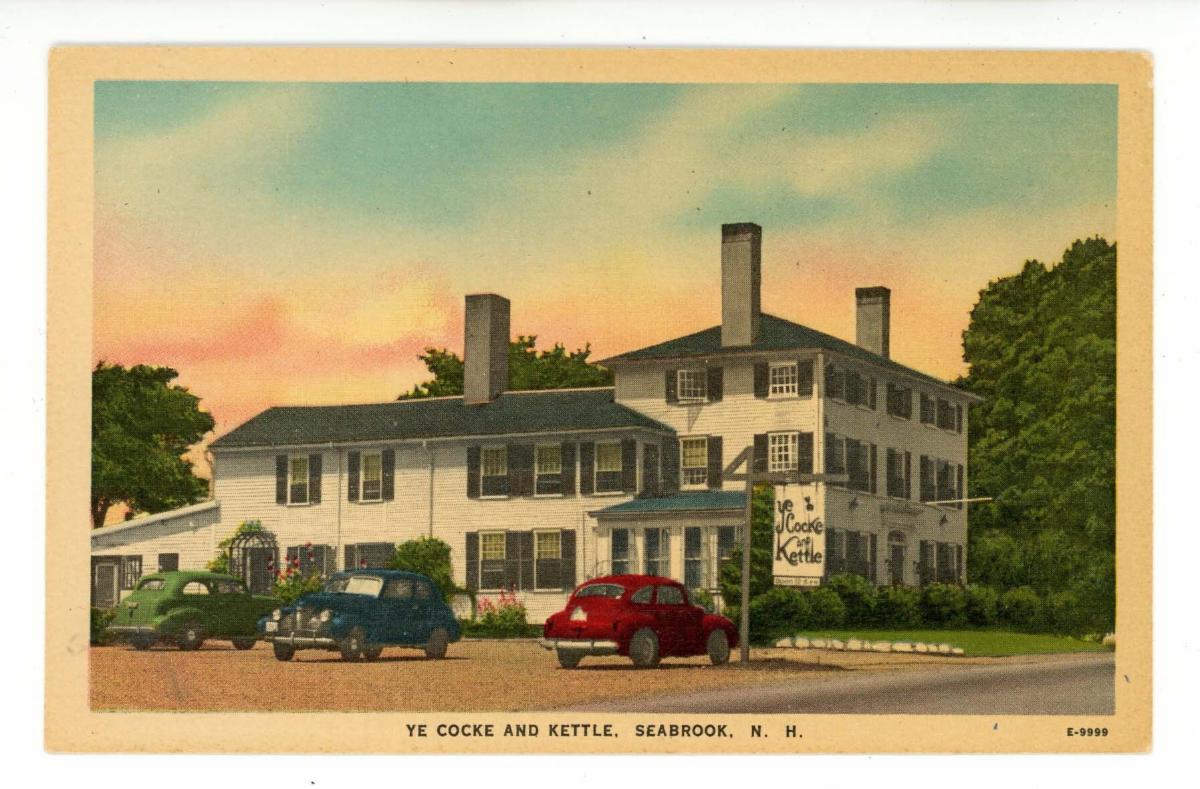

The mink farm craze spread to Amesbury, Salisbury, and by 1939, Mrs. Ethel Bradley of High Road, Newbury, was giving talks to the Ladies of the Rotary at Ye Cocke & Kettle in Seabrook on the subject of raising mink. In the West Newbury town report of 1956, there were 400 mink recorded, more than any other mammal.

To make a long, and to me, at least, fascinating story somewhat shorter, some mink escaped. Some farm owners, when faced with declining sales, released their captives rather than kill them and take a loss.

|  | Ye Cocke & Kettle, where Ethel Bradley gave a talk on how to run a mink farm to the Ladies of Rotary, May 17, 1939. | |

The 1956 West Newbury annual report showed 400 mink in town, more than any other farmed mammal! | |

|

The Minkette sailed out of Gloucester in its early days, catching fish to feed Newbury's captive mink. In later years, it became a fixture in Newburyport harbor, catching fish for other customers.

Credit: Newburyport Public Library Archival Center Bill Lane Photograph Collection

| |

|

One of the descendants of these captive mink, or perhaps a wild relative, a young, gorgeous thing, made its way to my farm two weeks ago, slipped right through the chicken wire, and killed three hens and a poor little floofy rooster named Admiral Nelson. And then he sat in the coop and waited for me to take his picture before slipping right past me and melting through the wire. It was otherworldly.

Of course, morbid curiosity sent me in search of the story of the mink farms that once dotted the landscape around here, and the more I read, the more fascinated I became. There were routine complaints from neighbors over the aroma of imprisoned mink, who give off a distinctly skunky musk, tales of the “Minkette I” whose sole purpose was to catch fish to feed the mink growing more luxuriant every day in Byfield. I cornered friends at cocktail parties and blathered on about mink farms, searched ship registers for the owner of the Minkette I, and thought perhaps this furry tale would a newsletter article make. And then, a chance encounter with my mother in our shared driveway sent the whole story sideways.

Picture this…

|  | |

My grandmother's cousin Mabel Noyes, right, with my great-aunt Louise Poore and her daughter Martha. Mabel's farm was turned over to mink after she died in 1960 and this connection sparked a family story from my mother. | |

|

I’m coming home from work, and my mother, who is leaving to run an errand, asks about the upcoming newsletter. She is a crackerjack editor, this mother of mine, and has done good service to the Museum of Old Newbury as a regular proofreader of the newsletter. I tell her that I’m thinking of writing about the Newbury/Byfield/West Newbury mink craze. She laughs. “You know my mother’s cousin Mabel Noyes’ house became a mink farm after she died.” And then, that look, a small smile, remembering her mother and visits to a memorable woman. “We used to bring her groceries. She was…” a pause and wrinkle of the nose… “a bit of a cat lady, and when she died, I remember cleaning out her house. She only lived on the first floor, and it was a mess, but the second floor was so tidy and nearly empty.” My mother tilts her head, looking up a bit. “She used to wear only basketball sneakers, no laces, cotton housedress. She was very nice – a little eccentric perhaps.” Then, trying to place Mabel in the family tree, we try to figure out who her parents were. “Silas,” my mom says. “Cousin Si. Did he die in a wagon accident? I’ll tell you a story about that if it’s the right Silas Noyes.”

I run into the house, open my laptop, find Mabel Ann Noyes, 1881-1960, never married, lived and died in her house at 2 Middle Rd. Byfield. Her father and brother were both Silas Noyes. Her father died in his bed in 1924. Not him. But her brother…

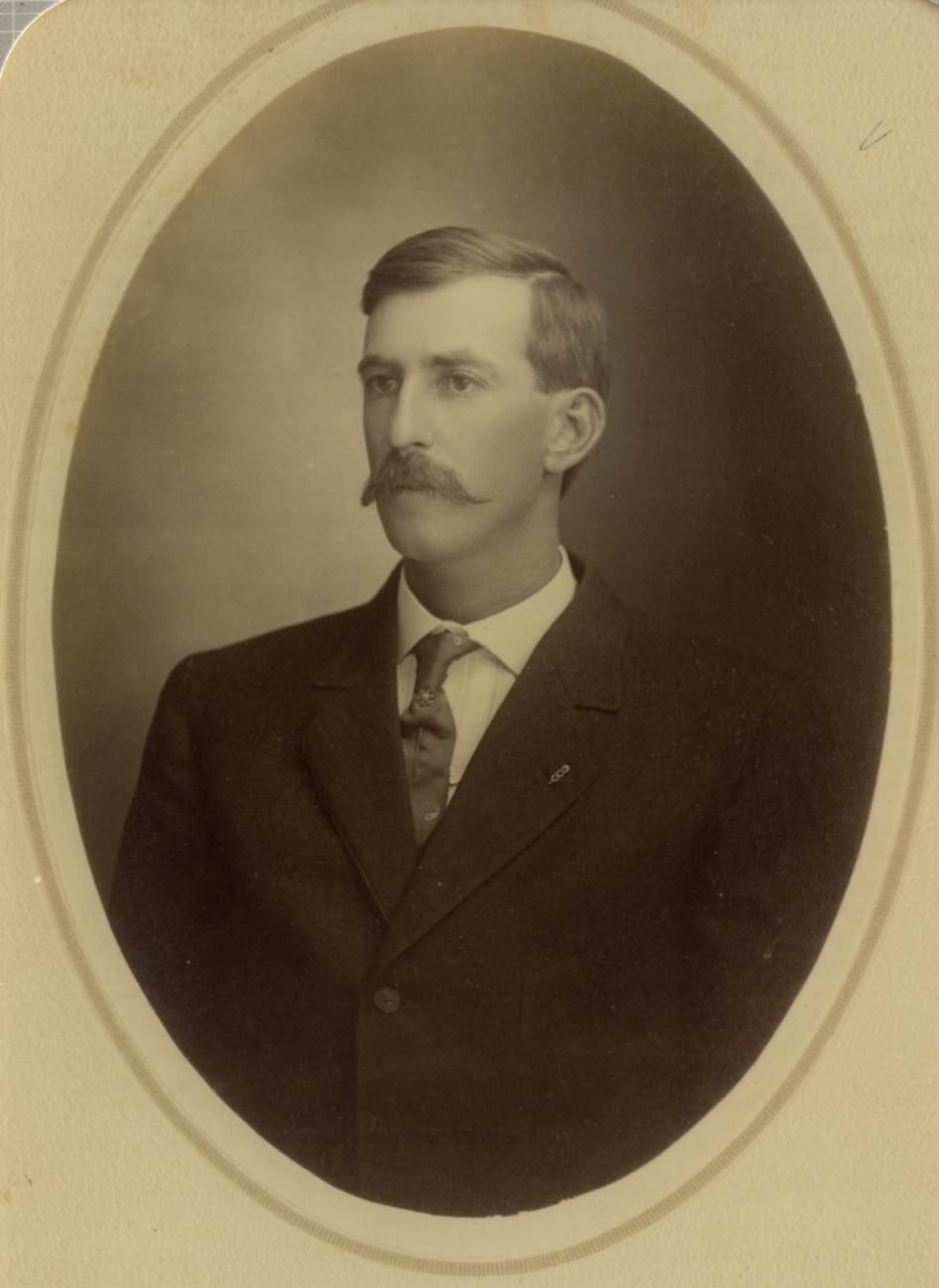

|  | Silas Dyer Noyes, 1880-1938, whose death in a tragic accident left a mark on the family. | |

Silas Dyer Noyes was born a year before Mabel. He was a farmer like his father, who was especially known for his cider apples. After his father died, the younger Si carried on farming, though times were hard enough during the Depression that he also took on paid work as a farm laborer and teamster, sometimes with the assistance of his nephew, William “Billie” Chipman Noyes Jr., born in 1929, who lived over on Boston Road.

Silas was a Freemason and Commander of the Odd Fellows in 1938, and he enjoyed the fermented fruits of his labor. “Aunt Emily told me about 'the men' drinking hard cider in the cellar at Cousin Si’s house when they gathered for various occasions,” my mother added. I know this would have been accompanied by a shake of the head from my great-aunt, who would not abide so much as cooking sherry in the house.

| |

Silas Noyes' death was front page news in Newburyport the following day, as was the regilding of the FRS weathervane, now in the collection of the Museum of Old Newbury. | |

|

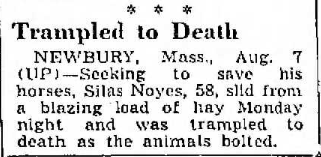

On August 7, 1939, as Silas was working with 10-year-old Billie on Orchard Street, the load of hay upon which he was standing caught fire, and as Silas, a life-long horseman, dropped down to unhitch the team and bring them to safety, they bolted. Silas was thrown, run over by the hay wagon, and killed.

The accident made national news, reported as far away as Utah and Nebraska. It was front-page news the next day in Newburyport, a tragedy that could so easily happen to any farmer.

“Billie started the fire,” my mother says. “He had been playing with matches behind the wagon - another family story is that he was sneaking cigarettes, but in either case it was the matches that started the fire. After the accident, the family got together and decided since he was just a boy, they would keep the cause of the fire that killed Cousin Si a secret.” It is notable that none of the articles about the accident mention the source of the fire, which was attended by Newbury, Newburyport, and Byfield fire departments, as well as a troop of Boy Scouts. There must have been some kind of official collusion in the keeping of this heavy secret. There was at least one other man working with Si and Billie that day, Wesley Ryan, but no mention of Billie. Perhaps in the chaos, he slipped away.

|  |  | Billie Noyes is on the left in this grainy family picture. News of his uncle Silas' death was reported as far away as Utah. | |

One month later, his sister Mabel oversaw the settlement of Silas Noyes' estate, which she inherited, and in which she lived and died. It became the mink farm of Alfred D. Smith in 1960.

Billie's parents separated soon after the accident and he moved to Florida with his mother. Billie and his brother Donnie kept in touch with Aunt Emily and her sisters. Whatever their childhood secrets, family is family, after all.

I sat with this story for a long while, wondering why it carried such weight for me. There was a death, of course, of a man who was trying to save his horses. This is enough to touch my heart. But there was something else. Billie Noyes carried the weight of that secret through his life, as far as one can tell from the record and other family members, manifested in numerous failed relationships, a violent temper and a general failure to thrive. My great-aunt Louise said only that he “did not make much of his life.”

I am sure that Billie’s involvement in Si’s death was kept by the family out of kindness and a hope to spare Billie the consequences of his youthful mistake, but secrets have a way of infiltrating the fiber of one’s life in a way that the truth does not. My mother grows thoughtful when she considers this. “There was no reason for anyone to tell me,” says my mom. “He moved away before I was born. What purpose did this serve but to perpetuate the secret, to make it my responsibility too? But secrets, especially family secrets, have an energy of their own. They want to come out.”

| |

Something Is Always Cooking... | |

|

Ted Lasso ‘Biscuits with the Boss’ Shortbread

Board member and MOON Costume Historian Lois Valeo recently baked these delightful shortbread biscuits, inspired by AppleTV’s hit show Ted Lasso, for us to sample. They were too good not to share!

1 C unsalted butter, softened, cut into pieces, plus more for greasing

2 C all-purpose flour

½ C granulated sugar

1 tsp. pure vanilla extract

½ tsp. fine sea salt

-

Preheat oven to 350 degrees. Grease a 9-inch square baking pan with butter. Line bottom and sides with parchment paper, leaving a 1-inch overhang on all sides. Set aside.

-

Beat butter, flour, sugar, vanilla, and salt with a stand mixer with a paddle attachment on low speed until mixture is well-combined and just beginning to come together, 45 seconds to 1 minute.

- Using your hands, press dough evenly into prepared pan. (If mixture is too sticky, place a sheet of parchment paper on top of dough, and press into pan. Remove parchment before baking)

-

Bake until edges are golden brown, 30 to 35 minutes. Remove from oven, and cool completely in pan, about 1 hour. Using parchment paper as handles, life biscuits from pan. Cut into 18 rectangles. Makes: 18 bars Active time: 10 minutes Total time: 1 hour, 40 minutes

| |

|

Click the image to do the puzzle

Ye Cocke and Kettle restaurant in Seabrook NH, where Ethel Bradley gave a talk on how to run a mink farm to the Ladies of Rotary, May 17, 1939.

| | |

Museum e-Newsletter made possible through the

generosity of our sponsors:

| |

| | | |