The Little Poconos Town That Accidentally Got Cool

A bunch of young, entrepreneurial cool kids are shaking up the rural northeast Pennsylvania town of Honesdale and turning it into a hot spot that could very well be the next Catskills. But with a now-cutthroat real estate market and an influx of city-weary crowds, how long can this charmingly small town stay ... small?

Rural Northeast Pennsylvania town of Honesdale. Photograph by Natalie Chitwood

He’s being nice about it — really, really nice — but I can tell Tim Meagher is ready to wrap up our time together. Wearing gray jeans and a crisp paisley button-down, with a hint of salt-and-pepper stubble washed across his broad face, he’s dressed for a day of getting things done. He’s spent the better part of this bright August morning winding me through Wonder, the complex of trendy Airbnb-style lofts he’s opening in a month. Designed by local artist Samuelle Greene, who’s worked on installations for the likes of Bergdorf Goodman and the Guggenheim, the spaces are bona fide Instagram catnip: Cool geometric murals cover the floors, and graphic wallpaper is splashed behind the beds. It’s the sort of style you’d expect to see in Fishtown, or Williamsburg, or Silver Lake — anywhere, really, other than where we actually are: Honesdale, Pennsylvania, a tiny whistle-stop — just four square miles — nestled in a woodsy Poconos valley in the northeastern tip of the state, about two and a half hours from both Philly and New York.

When you think of somewhere like Honesdale — you know, rural small-town America — you probably don’t think of hustle and bustle, of people zipping around in preparation for buzzy loft openings. But perhaps you should.

As a co-owner of RE/MAX Wayne — arguably the biggest commercial and residential real estate firm in this tiny town of just 4,300 — Meagher has had a front-row seat to a lot of Honesdale’s changes lately. (He’s actually sold most of the buildings they’re happening in.) Out on Main Street, Honesdale’s primary commercial artery, where American flags hang on nearly every block and the sensible square brick buildings never exceed three stories, once-empty storefronts are filling back up. Meagher has watched a work-boot shop become an art gallery and a dilapidated pharmacy morph into a craft brewery. Across the street from the hardware store, where the outdoor display of riding lawn mowers stretches almost two blocks, there’s now a coffee roastery and espresso bar.

This particular type of small-town transformation is nothing new. The story has been told many times over in Hudson Valley and in the nearby Catskills, where entrepreneurial urbanites looking for fresh air (and, let’s be honest, affordable real estate) have turned sleepy towns into nature-wrapped bastions of cozy restaurants, high-end home-design boutiques, and magazine-worthy farmhouse retreats.

Recently in Philly, I’d been hearing rumblings of similar happenings in the Poconos. Yes, those Poconos. The cheesy heart-shaped Jacuzzis and fusty wood-shingle ski chalets are still there, of course, but a new movement is rising. Burnt out on the city but too cool for cookie-cutter suburbs, young people are buying old houses out here, trading barre classes for long hikes and $15 avocado toasts for farm-fresh cheese, and breathing new life into the region.

For the past two decades or so, but especially for the past five years, Honesdale, the nexus of this movement, has been quietly evolving at an organic pace. But now, with vacation towns out West like Truckee, California, and Missoula, Montana, already seeing rocketing housing prices and being rechristened “Zoom towns” in Bloomberg because of their appeal to remote workers, Honesdale could spin into a new stratosphere. One that could change the paradigm between urban and rural life here in Pennsylvania — or, at the very least, bring them crashing together in new ways — but also threatens the homespun charm that makes this town wonderful in the first place.

Whatever lies ahead, it doesn’t change Meagher’s here and now. He’s been dealing with an influx of clients all summer, the bulk of them flooding in from Philly and New York. Some are fed up with city life and looking to relocate full-time, while others are desperately searching for a vacation home big enough for the entire extended family should there be a second quarantine. They can be a demanding bunch, so Meagher’s got to get back to drumming up new listings and putting the final touches on Wonder so it can start hosting visitors.

Because, like it or not, Honesdale is on the rise. And right now, in this era of COVID cabin fever and seemingly endless bad news, everyone wants in.

Ask anybody who’s been to Honesdale what’s cool about Honesdale, and they’ll probably tell you about Native. Owners Alex and Caleb Johnson met through the Safran Turney restaurant empire in Midtown Village — she was a front-of-house manager at Lolita and Little Nonna’s; he was the chef de cuisine at Barbuzzo. They married, had a baby, and dreamed of opening their own place. Just not in Philly.

“The city was already so glutted with restaurants,” says Alex. “We wanted to bring something new to where it would be needed.”

So they headed to Alex’s hometown, where, they’d heard, cool things had been going on. It seemed different from the Honesdale she grew up in — where everyone was the same, where there was nothing to do — but not different enough to stop the small-town gossip mill. Through the grapevine, the couple learned that Meagher was looking for someone to create a restaurant on the bottom floor of Wonder. Long and narrow, with plenty of exposed brick, the space reminded Alex and Caleb of the places they’d come up through in Philly. So they turned it into something you could pluck right off East Passyunk: exposed Edison bulbs, an open kitchen, an abundance of plants, and farm-to-table small plates — smoked duck rillette, broccolini Caesar — made with ingredients sourced almost exclusively from nearby purveyors.

Caleb and Alex Johnson. Photograph by Natalie Chitwood

The interior of Native. Photograph by Natalie Chitwood

Life in Honesdale is a nice change of pace for Caleb and Alex. Sure, their house may be the same size as the one they had in Point Breeze — two bedrooms, one and a half baths — but here, it comes with three and a half acres of land.

“We have a beautiful garden. We have 16 chickens. We have berry patches. Our kids go foraging with us,” says Alex. “In Philly, we’d have to drive two hours to go hiking or out on the river. Here, it’s in our backyard.”

The Johnsons aren’t the first of the so-called “comeback kids,” a moniker bestowed by a regional newspaper to a crew of Honesdale natives who left after high school but boomeranged back as young adults to put their stamp on Main Street.

“I never wanted to live here growing up,” Allaina Propst says of her hometown. “It was more monolithic — everyone talked the same, had the same path.”

Beers at Here & Now Brewing Company. Photograph by Natalie Chitwood

After stints at Goldman Sachs and a venture capital firm in New York, Propst returned home after her father’s death to help her mother — and decided to stick around. At age 23, she bought a run-down Woolworth Five & Dime with a combination of savings and a loan from a local bank. (“The loan process is 100 percent easier in a small town,” she says.) With the help of her cousin Steven Propst and brewer Karl Schloesser, she transformed it into a funky brewery and restaurant called Here & Now Brewing Company, which opened in 2017. Pre-pandemic, the scene was full-on Cheers: Every weekend night, Honesdalians — some dressed up, some dressed in camo — swept in to sip on small-batch saisons and IPAs. (As Propst will tell anyone who listens, it’s just not true that rural Pennsylvanians only drink Miller and Bud Light.)

“It became cool sort of on accident. It’s cheap enough that you can still make something, and a community happened around that.”

“This isn’t like upstate, where there’s all these New York expats that were fashion people or super-rich,” says Caitlin Cowger, who runs a suite of local cabin rentals — one of which Condé Nast Traveler just named one of the best Airbnbs outside of NYC. “It became cool sort of on accident. It’s cheap enough that you can still make something, and a community happened around that.”

That community is made up of people like Ryanne Jennings, 33, who returned to Honesdale after about a decade in Philly, where her family was busting at the seams of their Pennsport rowhome and ready for a break from the grind. She took over the Cooperage Project, a nonprofit that, pre-COVID, fueled the town’s packed roster of events, from farmers’ markets and concerts to after-school programs. (There were more than 350 listings in 2019 alone.) And there’s Travis Rivera, 38, who grew up in L.A. but headed to Honesdale in 2005 after his mother remarried a fellow with land here. A decade later, there still wasn’t a great coffee shop in town, so he built one. Black & Brass now has two locations: the original at 5th and Main, and a second, larger spot — one with a friggin’ waterfall in the back — that opened last October. Two more are in the works.

Second District Vineyard. Photograph by Natalie Chitwood

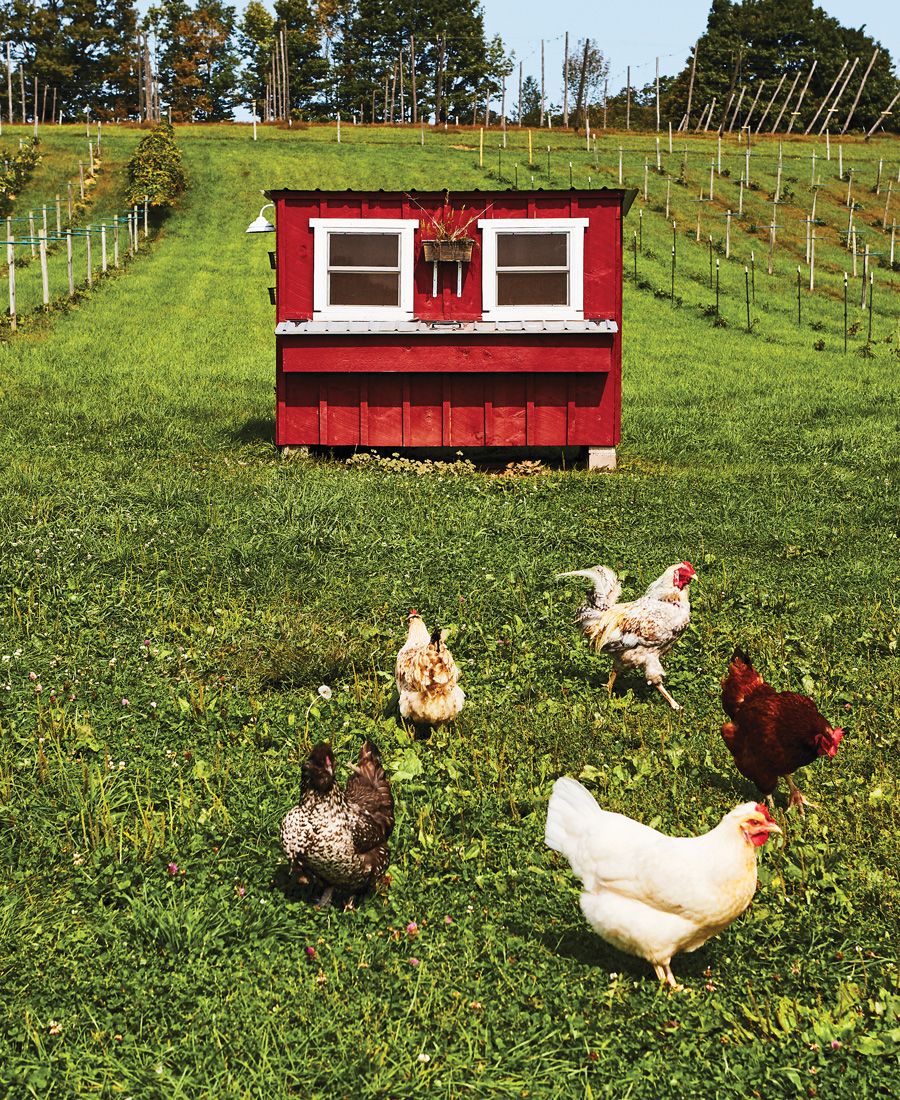

Scotty Kurtain, meanwhile, was lured to Honesdale by Philly real estate developer John Longacre, who owns American Sardine Bar, South Philly Tap Room, and Second District Brewing. Longacre is perhaps best known for investing in Point Breeze and Newbold when most of his peers were staying far away, so it probably bodes well for Honesdale that his latest venture is a spot called Second District Vineyard, located just 20 minutes outside of town. Longacre bought the place in 2014 and eventually recruited Kurtain, a former barback at South Philly Taproom, to transform it into a farm for his restaurants. Kurtain didn’t know much about agriculture when he arrived, but he’s turned the place into a thing of beauty. When I swing by at the suggestion of his wife, Arrah Fisher, who succeeded Ryanne Jennings at the Cooperage last October, tidy lines of Chinook hops grow up coconut twine hung from sturdy wood beams. Chickens cluck in and out of a coop situated just below a patch of grapevines. Pumpkins the size of beach balls sprout next to leafy stalks of kale in the vegetable garden, and apple trees — their fruit will be fermented for hard cider — grow in the on-property orchard. Complete with a barn, a private pond and a wine cellar, plus a few overnight cottages that are in the works, the property is the perfect backdrop for events like the weekend wine tastings and local-maker markets that Longacre plans to run once the world returns to a semblance of normal.

“It isn’t at all what I thought it would be,” Longacre says of the region. “It’s much, much cooler. And when you combine the fact that you’re right on the New York border to Narrowsburg and Callicoon, which are their own ridiculously cool little towns, and you look at the population that comes up here in the summer — lots of people from NYC, lots of people from Philly — it just seemed like a very untapped area that was ready to go.”

Olivia Santo at Gather. Photograph by Natalie Chitwood

The list continues. There’s Gather, a stylish clothing and gift shop from Olivia Santo, a former corporate merchandise planner at Macy’s. Jeff Abella and Ishan Tigunait run Moka Origins, a bean-to-bar chocolate and coffee company that was spotlighted earlier this year in the New York Times, and people come from as far as South Korea to get inked by Dan Santoro, the NYC-famous tattoo artist who runs a shop in nearby Hawley. (There’d be even more to discuss — like sandwich shop Alley Whey and events at art gallery Basin and Main — but, you know, coronavirus.)

These new additions, sprinkled in among the appliance shops and thrift stores of old Honesdale, create a little melting pot of urban amenities and small-town charm, sandwiched by resplendent greenery on either side. Even on a short visit, it’s easy to see the appeal.

In many ways, Honesdale was primed for this recent evolution. Entrepreneurialism is, after all, baked into its very beginnings, when, in the early 1800s, Philadelphia businessman William Wurts began buying parcels of land in the area to mine anthracite coal. Wurts wanted to send the stuff back to his home city, but Lehigh Valley beat him to the punch. So he about-faced to New York, where the coal supply had been short since the War of 1812. To get it there, he’d need a canal — and a pretty big one at that. But he made it happen. Together with brothers Maurice and Charles and investors including future company president and Honesdale namesake Philip Hone, Wurts founded the Delaware & Hudson Canal Company in 1823. Their project — one of America’s first million-dollar private enterprises — was a 108-mile waterway that began at company headquarters in Honesdale, where coal arrived from the nearby mines of Carbondale via gravity train, then stretched along the Lackawaxen and up the Delaware, eventually streaming into New York’s Ulster County, where the rocks were loaded onto Hudson River steamships, floated south to Manhattan, and literally fueled the Industrial Revolution. (Philip Hone, by the way, went on to become the mayor of New York.)

A mural on the RE/MAX Wayne building. Photograph by Natalie Chitwood

As the seat of Wayne County, Honesdale also already had a lot of the infrastructure necessary for a renaissance: decent-size hospital, government buildings with white-collar government jobs, three regional bank headquarters, a nearby Walmart. There were even a few pre-existing doses of quirk and cool: Highlights, once America’s most popular children’s magazine, was founded here in 1946 (the editorial offices are still in town), and the Himalayan Institute, a massive yoga retreat, sits on the outskirts of the borough.

The entrepreneurial spirit is still alive and well, and even local government is getting in on the momentum. In 2015, Wayne County partnered with a local economic development org to launch the Stourbridge Project, a free co-working space and small-business incubator housed in a repurposed Honesdale elementary school. It’s got good internet (the highest bandwidth in the county; more on that later), digital media studios, private conference rooms, and 3-D printers and laser cutters for prototyping. (It’s even got a “Maker in Residence,” Lisa Glover, who will teach you how to use it all.)

Encouraging entrepreneurialism, especially in tech, is the whole goal of this place. Director Susan Shaffer wants Honesdalians to build their businesses here, and she wants other businesses to relocate here. (A printing services company and a health-care staffing brokerage already have.) It’s a road map for what could happen in other rural towns in the state, so forward-thinking that it was named the Pennsylvania Economic Development Association’s Project of the Year in 2018.

Still, this isn’t entirely some hidden little utopia in the making. Problems do exist. Like the winters, which are brutal (unless you’re into that sort of thing). Like the homogeneity. (Wayne County is predominately white.) Like poverty and addiction, issues that much of rural America (and Philly, for that matter) grapples with. Like the Internet, which can be slow. (This might seem like a paltry complaint, but it’s actually a well-documented roadblock to rural development. As the economy globalizes and we continue to shop, work and, really, live online, more remote towns could be left out entirely without proper wiring.)

What’s more, some easy-to-take-for-granted aspects of more densely populated areas can be hard to come by. (“You can’t necessarily be anonymous here,” says Propst. “I can’t get drunk and dance on the table, because everyone knows me.”)

“You can’t necessarily be anonymous here. I can’t get drunk and dance on the table, because everyone knows me.”

The population also skews older — per the most recent census estimates, a quarter of the residents are 65 and above, and yes, a bulk of them voted for Trump the first time around. But while you might assume the interplay of old Honesdale and new (more liberal) Honesdale would throw off sparks, that isn’t really the case. Sure, some older folks don’t understand everything about what the young ’uns are building — Native, for example, faced some resistance over its portion sizes because people weren’t used to sharing small plates — but where doesn’t that happen? In fact, when I ask Carol Dunn, the 70-year-old director of the Wayne County Historical Society — the very keeper of Honesdale’s past — what she thinks about the future, she’s excited.

“I see Honesdale as hustling and bustling,” she says. “I see an economy created by a younger generation that far surpasses the retirees. They’ve taken it and run with it. Made it their own. I see Honesdale capably in the hands of another group of people, and they’re not hankering for what used to be.”

If Honesdale’s renaissance comes as a surprise to you, it shouldn’t. At least, not according to University of Minnesota rural sociologist Benjamin Winchester, who has spent his nearly 25-year career telling everyone how outdated the rural narrative — struggling farms, emptying towns, retirees at the VFW — truly is. In reality, America’s rural population is growing (up 11 percent since 1970), with a diversifying economy. (Ag, extraction and manufacturing used to dominate, but today it’s education and health services.) What’s happening in Honesdale right now is actually much closer to the rule than the exception.

And while talk of “brain drain” — high-school and post-high-school-age kids leaving in search of opportunities in urban areas — still holds up, Winchester is much more concerned with the movements of 30- and 40-year-olds, like the ones reshaping Honesdale, who are in their prime earning years. The brain gain, as he calls them. On a national level, this age group is growing in rural communities. (In Wayne County, the percent cohort change — the growth of a specific age range over time — for these groups was up an average of 30 percent between 2000 and 2010.)

Some alarmists are already predicting the pandemic will speed up this trend — that those with means and jobs that can be done remotely will abandon urban centers for small towns and bring about the demise of cities in the process. But what’s more likely, at least in the near term, is that those with means will just start splitting their time more evenly. With fewer reasons to actually be anywhere other than in front of their computers, urbanites will spool out weekend visits to the country into month-long stints. That means they’ll need a comfortable place to stay.

Which brings us back to Tim Meagher’s busy summer. As we walk the two blocks from Wonder to his office, he tells me more about the deluge of emails and phone calls he’s been fielding. They’re from people in their 30s, 40s and 50s. They’re largely on the hunt for second homes, and they know they can snag a whole lot of square footage up here for between $200,000 and $500,000. If they’re from Philly, they’ve typically vacationed at the Shore, but they’re worried about the Shore closing down again. In Northeastern PA, where you often have lake access rights or own your lake frontage and many properties come with ponds, you’ll never be shut out of the water.

It’s a cutthroat market — something Northern Liberties home stager Kendall Quigley knows firsthand. Originally interested in a Catskills retreat, she turned her attention to NEPA in March because of its proximity to Philly, low property taxes and even lower prices ($70K for an A-frame! $90K for a ski chalet!). But those prices have been steadily climbing this year — per data from Redfin, the median sale prices for homes in rural areas nationwide increased 11.3 percent year-over-year for July — and she lost out on eight bids before finally securing the keys to a cabin on Hawley’s Paupackan Lake in September.

“It’s so competitive, it’s insane,” she says. “It’s not only us Philadelphians who are like, Let’s bring back the Poconos! All these New Yorkers are also seeing the potential. And a lot are buying with cash.”

It’s too soon to tell what this all means for Honesdale. Can it continue to grow by itself, for itself, without succumbing to the wants of part-time inhabitants? Or does it become the next hot upstate-adjacent escape, one where the hearing-care center is replaced with a Pilates studio and the music equipment store becomes a juice bar? Or is a new model in order, one in which city folk and rural folk finally, actually participate in the same community and finally, actually start talking to one another, instead of yelling into the echo chambers of Facebook and Instagram?

That’s what’s so exciting about Honesdale right now: possibility. We’re still early enough to be asking these questions, waiting to see how it all unravels. Still, everything has its tipping points.

“I just hope it’s good change,” says tattoo artist Dan Santoro when I ask him about what comes next. “I lived in New York for most of my adult life. Now that I’ve experienced this way of living, I really don’t want to go back to that. So if it gets to the point where people are demanding their Starbucks and it’s just strip malls and condos here, I have to keep moving.”

Published as “The Little Poconos Town That Could” in the November 2020 issue of Philadelphia magazine.