Add Your Voice: Respond by

March 22

CEI School Climate Validation Study |

|

|

|

Alienation - Youth who are deeply troubled

|

|

A difficult time. A difficult topic with tragic reper-cussions. Check out this Scientific American article.

|

|

|

|

Dear Educators,

Think about it. If you were given the opportunity to develop goals that might inform how you spend your time, what goals would you choose? How would you know you made a good decision? Are there times when you might be more "in-tune" with what might be best for you? While self-determination was originally all about helping oppressed people take control of their lives and their destiny, today it is an important component of the IEP/transition process for students with disabilities.

In this month's Wow!Ed , CEI Board member and researcher, Dr. Sharon Field, and I take a glimpse at the history self-determination, explain how it is used with student-led conferences and IEPs, and suggest how mindfulness can enhance understanding of self. Also in this month's Wow!, Marah Barrows reviews two mindfulness scales that are appropriate for teachers and youth. |

|

Self-Determination: From the Fight to Gain Basic Rights to the Power of Student Voice

By Sharon Field and Christine Mason |

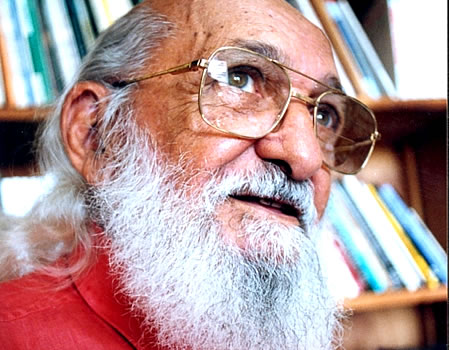

Self-determination - a powerful concept. Paulo Freire, a revolutionary thinker in Brazil, who was frustrated by the poverty he saw, described the need for those who are oppressed to become literate, gain self-agency, and participate in decisions about their own lives

-- in essence, to be self-determined (1968). Freire emphasized the critical importance of literacy in preparing students not for "the world of subordinated labor or "careers," but [as] a preparation for a self-managed life." (Aronowitz, 2009).

Historically, civilizations, nations, and indigenous people have fought for the right to be self-determined (Daes, 2008; Hannum, 2011; Manela, 2007). Some have faced a life-time of struggles; others live in areas that have inherited centuries of conflict and restrictions to their basic human rights. In 2007, the United Nations declared the

rights of indigenous people, including: "the right to self-determination" (Article 3), but many still have not reclaimed their rights and status.

Self-Determination for All

The need for self-determination has often been highlighted for oppressed groups because they suffered from a lack of control over their lives. However, self-determination is crucial not only for countries or oppressed groups, but for all individuals. Self-determination is based on the degree to which three basic psychological needs (autonomy, competence and relatedness) we all possess are fulfilled (Ryan & Deci, 2000). When these needs are met, self-determination leads to increased motivation, productivity, happiness, and sense of well-being. Not only is self-determination needed to overcome adverse circumstances and oppression; it is also needed to thrive and excel.

So, to be self-determined means that you are aware of your own strengths, weaknesses, desires and options. You believe in your right to pursue them and can set your own goals. You have more control over your life - your work, your housing, your friends, and how you spend your time.

Self-determination is as important today as it has been historically, for youth as well as adults. Consider one of the significant outcomes of the horrific tragedy at the Marjory Stoneman Douglas School in Parkland, FL in February 2018: Students have begun to assert their self-determination in their fight for legislation on gun control in their urgent quest to make their schools safer places for them to learn and grow.

Self -Determination for Students with Disabilities

In schools, one of the groups that has been underserved, and until the passage of the Education for All Handicapped Children's Act in 1975, even excluded from public education, is students with disabilities. Historically, these students and their families have had little say about decisions that have had a major impact on their lives. Individuals with disabilities have been excluded from decisions about where they would live, what they would do for recreation, and what, if any, kind of work they would do. In the 1980's and 90's, they began to assert their right for self-determination through legislative and educational initiatives. "Nothing about me without me" became a rallying cry and:

- Legislation was passed that required that students be invited to transition planning meetings when decisions were being made about their educational programs and futures.

- Adults with disabilities became involved in decisions about how money was being spent by government agencies on their behalf.

- Funding was provided to develop supports for instruction related to self-determination in public schools.

Goal Setting and Self Determination: The How

Thankfully, since the 1980's and 90's, self-determination for students with disabilities has meant that they have a say in their education -- in what they study, in the supports they receive, and in how they participate in planning for their futures. For students, a primary way in which self-determination has been implemented has been through their involvement in their own IEP meetings -- in some ways almost the ultimate in personalized instruction.

- Students meet with support teams and identify their own IEP goals, monitor their own progress, and learn about options that might be most appealing to them.

- Through this process, students become more engaged in their education and in making decisions that will often have life-long repercussions.

Many schools have looked at the need for self-determination for all students and have initiated student-led conference throughout their programs. In addition, educators have begun to examine the ways in which they provide students with choices throughout the school day. They are also providing instruction to help students develop skills that will help them make informed choices based on their needs and wants. (Field & Hoffman, 2002)

Leading IEP Meetings. Leading IEP Meetings. Over the past 30 years, we have worked with numerous schools on helping individuals direct their own IEP meetings (Mason, McGahee-Kovac, & Johnson, 2004: Test, Mason, Hughes, Konrad, Neil, & Wood, 2004; Wehmeyer, Field, Doren, Jones, & Mason, 2004). During this time, we have seen students with cognitive deficits learn to talk about their disabilities and ask for accommodations. We have observed many positive differences in IEP meetings where students are included as important participants:

- When adults listen to what students say they want, it is much more compelling and real than if the same goals are stated by one of the adults in the room.

- It is powerful for students to state what they want and they are much more likely to remember and act on their stated goals if they played a role in choosing and then stating them to others.

The preferred role for the student in the IEP meeting is to chair the meeting, when possible. However, many students may not feel comfortable in that role initially or have the skills needed. There are many ways in which students can be included in their own IEP process. Students sometimes initially become involved in their own IEP meetings by simply attending and responding to questions.

How the IEP Process Changes When We Listen to Students

When students are actively involved in their IEP process, we may see differences in the tone and tenor of the meeting, feelings of pride and commitment experienced by students, and role changes experienced by all participants. For example, after a student with a severe cognitive disability and no verbal language skills participated in her IEP for the first time, the IEP team members reported positive differences in both the planning process and also outcomes of the meeting. In prior years she had not been invited to her meeting -- teachers had previously underestimated the student's capacity to participate in her IEP process. This year, the teacher obtained input from the student prior to the meeting. The student was able to verify the accuracy of the information and respond to questions about it during the meeting. Adults reported that they behaved differently at the meeting. They took time to explore what would be in the student's best interest and, respectful of the student's needs, they didn't simply rush through the protocol of reaching an agreement on goals and getting signatures of the IEP team members.

References

Aronowitz, S. (2009) "Forward" in S. Macrine, ed.

Critical pedagogy in uncertain times: Hope and possibilities. New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2009, pp. ix.

Daes, E. I. A. (2008). An overview of the history of indigenous peoples: self-determination and the United Nations.

Cambridge Review of International Affairs, 21(1), 7-26.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being.

American Psychologist, 55(1), 68-78

Field, S. & Hoffman, A. (2002). Preparing youth to exercise self-determination: Quality indicators of school environments that promote the acquisition of knowledge, skills and beliefs related to self-determination.

Journal of Disability Policy Studies, 13, 113-118.

Hannum, H. (2011).

Autonomy, sovereignty, and self-determination: the accommodation of conflicting rights. University of Pennsylvania Press.

Manela, E. (2007).

The Wilsonian moment: Self-determination and the international origins of anticolonial nationalism. London: Oxford University Press on Demand.

Mason, C., McGahee-Kovac, M., & Johnson, L. (2004). How to help students lead their IEP meetings.

TEACHING Exceptional Children,36, 18-24.

Test, D., Mason, C., Hughes, C., Konrad, M., Neale, M., & Wood, W. (2004) Student involvement in Individualized Education Program meetings: A review of the literature.

Exceptional Children,70, 391-412.

Wehmeyer, M. Field, S. Doren, B. Jones, B. & Mason, C. (2004). Self-determination and student involvement: Standards- based reform, access to the general curriculum, and CEC's performance-based standards.

Exceptional Children, 70, 413-425.

Sharon Field is Professor Emeritus at Wayne State University, Founder of 2BSD, and a CEI Board Member.

|

|

Increasing Efficacy- Pairing Self- Determination with Mindfulness

By Christine Mason and Sharon Field |

Imagine going through life with someone else, perhaps a parent, making most of your life decisions for you - setting your alarm clock, deciding on your diet, overseeing which movies you attend, your friends, your wardrobe, your bank account. Perhaps even deciding on your job, your work schedule, choosing your car, your vacation, selecting your mate, and even supervising your doctor and dentist appointments. How would you feel? Now imagine that you are 13, and someone else is deciding the topic of the paper you will write, when you will study, whether you should try out for basketball, or whether you should ask for additional help with a class. Students who at 13 are given little choice regarding their activities, may find themselves guided by a parent/mentor/coach/guardian/supervisor for their entire lives. This is certainly the antithesis of self-determination.

Student Voice

In

Speak, Laurie Haldeman begins her tale of her life: "It is my first day of high school. I have seven new notebooks, a skirt I hate, and a stomachache." (p.1).

Speak is a novel for teens that relates the angst of high school, including the sense of loneliness and alienation that many feel. Author Benjamin Connor (2012) begins his book on the lives of adolescents with developmental disabilities with "I found Edward sitting alone at one end of a table made for sixteen. Asperger's syndrome is a particularly challenging condition for kids who long to be connected with their peers. . . As I sit across from him, Edward opens, "This is a table for misfits because I am a misfit." (p. 1-2). John O'Brien, in

Person Centered Planning says, "None of us creates our lives alone." (p. x) Michael Smull in that same book writes, "when you put ... planning for your future and control of resources together you have self-determination." (p.4)

How can Teachers Help with Self-Determination?

As we implement self-determination for youth with disabilities in schools, it may help us to consider, how can we best help these youth become self-determined? How can we best help them express their strongest desires and priorities? The girl in Haldeman's story knows she wants a different life. What would that take? The boy in Connor's book yearns to be accepted, to fit in. What would that take? What are the resources that are needed and how should that planning occur?

Not knowing. Some students with disabilities will readily know what they want, or they may think they know until their universe expands and they look at other options. At that point some may change their minds. Perhaps you have worked with students who are like this - individuals who really like best the last thing that they experienced. Other individuals with disabilities may be uncertain about what they want. They will need more information about their options.

When it comes to helping youth find employment, we have developed a process, a science, of transition planning. Youth take assessments, study about their options, and have a few on-the-job experiences before determining their preferred job. However, we do not use as much science with housing, recreation, or other leisure activities. Sometimes it is trial and error, and sometimes decisions are made largely on what is available, and largely by others on behalf of the student.

The power of mindfulness. There is a tool, however, that we could add to our self-determination toolbox that might help improve the efficacy of this decision-making process -- mindfulness. Mindfulness or "the awareness that arises by paying attention on purpose in the present moment nonjudgmentally" (Williams, Teasdale, Zindel Segal, & Kabat-Zinn, 2007, p. 7) contributes to increased self-awareness. Such self-awareness, as well as a "mindful" understanding of one's surroundings, is essential to self-determination. Yoga, meditation, and visualization can increase mindfulness. Learning to breathe deeply quiets the mind and helps to get rid of the internal chatter that may interfere with clarity. If students with disabilities and their support teams are intent on using time wisely to help students learn more about themselves and their preferences, it seems that mindfulness may be an ideal tool to help expand students' conscious understanding of themselves and others.

Mary Davenport describes

how she implemented mindfulness practices in her high school classroom. At the beginning of each class session, after greeting students, she would remind them of the ways they had practiced mindfulness including mindful listening, diaphragmatic breathing, gratitude journals, progressive muscle relaxation, affirmations, etc. She would then begin the mindful moments practice by guiding students into a space of mindfulness where they would most often pay attention to their breathing, but sometimes would focus on ambient sounds, emotions, or a mental activity. Her students reported that mindfulness helps with stress, confidence, relationships, communication, metacognition, health, and focus. Each of these areas are clearly related to helping students meet their needs for autonomy, competence and relatedness as defined by Deci and Ryan (2000) and to developing the personal competencies of the

Action Model of Self-determination (below; Field & Hoffman, 2015).

Inserting Mindfulness into the Action Model for Self-Determination

Sharon Field and Alan Hoffman developed

The Action Model for Self-determination (2015) to guide teachers as they help students develop the knowledge and skills that contribute to their self-determination. This Action Model can assist teachers and schools as they apply science to helping students become self-determined. If students are at a place where mindfulness might assist them in learning about themselves, then mindfulness exercises and activities can be inserted into the first steps. For example, we may have students do some simple breathing exercises before asking question about their preferences. Or we may even develop a guided visualization where students with eyes closed imagine working at different jobs or living in different parts of the city.

The Action Model has five major components. (See Figure 1.)

- Know Yourself and Your Context and Value Yourself describe internal processes that provide a foundation for acting in a self-determined manner.

- The next three components, Plan, Act, and Experience Outcomes and Learn, identify skills that an individual needs to act on this foundation.

In order to be self-determined, individuals need to know what they want, believe in themselves

and take concrete steps to achieve what they desire. With this model the ideal place to insert mindfulness is right at the first steps as individuals learn more about their own preferences and desires.

A Footnote on Teacher Self -Determination

As we worked with schools, we found that some teachers didn't really understand self-determination. These teachers were typically less assertive and more likely to simply comply with district and school mandates and expectations when compared to other teachers in their schools. Teachers who had not yet found their own voices were less inclined to facilitate self-determination for their students. After we realized what had happened, we developed protocols, tools, and suggested strategies for teachers to become self-determined -so that they become more empowered themselves. (Field & Hoffman, 1996; Field & Hoffman, 2002; Wehmeyer & Field, 2006).

What is the Future of Self-Determination?

Today, with 21st Century technology, individual education programs are taking hold for many students, with and without disabilities. Many schools are building off of what they have learned through the IEP process as they consider individual plans for each student. Exploring options, developing and monitoring goals, and providing supports are all helpful. Almost on a parallel track these past five years, mindfulness has emerged as a major initiative to help students learn faster, more efficiently, and feel better about themselves. Results to date of a merger of these initiatives give us reason to believe there is more to come - that greater self-determination will be realized when mindfulness is inserted as part of Step #1. We urge teachers to get involved themselves in mindfulness and self-determination. Those teachers who use these tools in their own lives will be better prepared to introduce these to their students as well.

References

Connor, B. (2012).

Amplifying our witness: Giving voice to adolescents with disabilities. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans.

Davenport, M. (2018, February 1). Mindfulness in high school.

Edutopia.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The" what" and" why" of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior.

Psychological inquiry, 11(4), 227-268.

Field, S. & Hoffman, A. (2015). An Action Model for Self-Determination. Revised from "Development of Model for Self-Determination," by S. Field and A. Hoffman, 1994,

Career Development for Exceptional Individuals, 17(2), p. 165.

Field, S. & Hoffman, A. (1996). Increasing the ability of educators to support youth self-determination. In L.E. Powers, G.H.S. Singer & J. Sowers (Eds.),

Making our way: Building self-competence among youth with disabilities. Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes.

Field, S. & Hoffman, A. (2002). Lessons learned from implementing the

Steps to Self-Determination curriculum. Remedial and Special Education 23,(2), 90-98.

Haldeman, L. (2011). Speak. Bel Air, CA: Square Fish.

O'Brien, J. & O'Brien, C. (2002).

Implementing Person-Centered Planning. Toronto, Ontario: Inclusion Press.

Wehmeyer, M.L. & Field, S. (2007).

Instructional and assessment strategies to promote the self-determination of students with disabilities. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Williams, M., Teasdale, J., Segal, Z., & Kabat-Zinn, J. (2007). The mindfulness way through depression. New York: Guilford Press.

|

|

Joining the Two: Where Mindfulness Meets Self-Regulation

By Marah Barrow, CEI Intern |

A conscious understanding of what is happening in the here and now is an essential element of mindfulness. In other words, conscious mindfulness allows individuals to separate their actions, emotions, and thoughts from what is in reality happening to them and how that, in turn, influences their external actions. This mindful separation permits individuals to make informed choices with conscious awareness of their feelings and emotions.

How to Assess Mindfulness

MAAS. Several short, low-cost/no-cost scales are available to assess mindfulness. One of the most widely used scales, the

Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS), developed by Brown and Ryan (2003), provides evidence that mindful thought leads to increased emotional awareness (Sivanathan, Arnold, Turner, & Barling, 2004). The validity of MAAS for use with adults has been substantiated by numerous studies. However, a few studies have been conducted with youth, and versions of MAAS are available for children (MAAS-C) and adolescents (MAAS-A). In one recent study conducted in Chengdu, China, MAAS' validity with Chinese adolescents was confirmed (Black, Sussman, Johnson & Milam, 2013). This particular study reinforced the idea that mindfulness decreases mental health concerns and shows potential for its application to reduce disruptive and inappropriate behaviors.

Examples from MAAS demonstrate the range of ways in which MAAS asks respondents to consider the quality of their mindful attention:

- "I find it difficult to stay focused on what's happening in the present."

- "I rush through activities without being really attentive to them."

- "I find myself preoccupied with the future or the past."

With MAAS, using a 6-point Likert scale, respondents rate their level of awareness, and their demonstration of mindfulness components, such as receptiveness and awareness to the present. By assessing this level of consciousness, individual behavioral, emotional, and interpersonal responses can be discerned more reliably (Brown, et al. , 2003). A short version with six items is also available.

Five Facets. Another measure, the

Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (Baer, Smith, Hopkins, Krietemeyer, & Toney, 2006) assesses mindfulness characteristics using a 5-point Likert Scale to assess nonreactivity, observing, acting with awareness, describing, and non-judging. Examples of each of these follow:

- Nonreactivity

- "I perceive my feelings and emotions without having to react to them."

- Observing

- "When I take a shower or bath, I stay alert to the sensations of water on my body."

- Acting with awareness

- "I find myself doing things without paying attention."

- Describing

- "It's hard for me to find the words to describe what I am thinking."

- Non-judging

- "I make judgements about whether my thoughts are good or bad."

The

nonreactivity component of the

Five Facets questionnaire rates an individual's ability to react in a calm way when confronted with an experience that may appeal to certain emotional responses. An individual's ability to observe measures self-awareness of thoughts and feelings.

Presence of mind is reflected by an individual's ability to act with awareness.

Descriptive characteristics distinguish the ability to determine the types of emotions and feelings an individual may be experiencing. Finally, the

non-judging facet of the questionnaire determines degree to which emotions impact an individual's ability to remaining objective.

Does Mindfulness Lead to Increased Ability to Self-regulate?

According to Baumeister and Vohs (2007), self-regulation consists of the four following components:

- Standards: Appropriate behavioral response

- Monitoring: Measuring oneself against a set standard

- Willpower: Impulse control

- Motivation: Goal achievement

Emotional self-regulation, Emotional self-regulation, an important component of self-regulation, is the key to responding to situations with less impulsivity and an increased sense of emotional self-control (Sivanathan et al, 2004). To promote healthy situational responses, self-regulation, which is knowingly linked to components of mindfulness like self-knowledge and present-consciousness, plays an integral role. In essence, when people have a sense of autonomy, a hyper-focus on situational demands will not hi-jack their ability to react in ways that are beneficial to themselves and/or others (Sivanathan et al, 2004).

Self-regulation and emotional responsibility. Emotional self-regulation is essential to maintaining a sense of emotional responsibility, thus separating emotion from action or reaction (Stosny, 2011). By becoming more aware of one's values, individuals are better able to avoid the negative feelings and emotions that come with a violation of values. This is in and of itself is the practice of self-regulation (Stosny, 2011).

Measuring Self-Regulation

Brown, Miller, and Lawendowski (1999) developed the Self-Regulation Questionnaire. Using a Likert scale, individuals rate their own self-regulatory behavior with items such as the following:

- "I usually keep track of my progress towards my goals."

- "My behavior is not that different from other peoples'."

- "Others tell me that I keep on with things too long."

Mindfulness Enhances Self-Regulation

As individuals become more attuned to their personal well-being, emotions, values, and feeling, they are better able to self-regulate and to consciously choose active, rather than reactive, responses as they navigate their day-to-day lives (Sivanathan et al, 2004). By using mindfulness strategies, the constant pull towards reactiveness is minimized. Individuals are given more power and freedom to respond to cultural and situational demands in a constructive manner (Sivanathan et al, 2004).

References

Baer, R. A., Smith G. T., Hopkins, J., Krietemeyer, J. & Toney, L. (2006).

Using self-report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness.

Assessment, 13(1), 27-45.

Baumeister, R. & Vohs, K. (2007). Self-Regulation, ego depletion, and motivation. S

ocial and Personality Psychology

, 115-128.

Black, D. S., Sussman, S., Johnson, A., C., Milam, J. (2011).

Psychometric assessment of the Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS) among Chinese adolescents.

Assessment, 19(1), 42-52.

Brown, J. M., Miller, W. R., & Lawendowski, L. A. (1999).

The Self-Regulation Questionnaire. In L. VandeCreek & T. L. Jackson (Eds.),

Innovations in clinical practice: A source book, 17, 281-289. Sarasota, FL: Professional Resource Press.

Brown, K.W. & Ryan, R.M. (2003).

The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being.

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84, 822-848.

Sivanathan, N., Arnold, K. A., Turner, N. & Barling, J. (2004)

Leading well: Transformational leadership and well-being, in P.A. Linley and S. Joseph, eds.

Positive Psychology in Practice. Hoboken, NH: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. doi: 10.1002/9780470939338.ch15

|

|

|

To Become Themselves

Paulo Friere said, "The teacher is of course an artist, but being an artist does not mean that he or she can make the profile, can shape the students. What the educator does in teaching is to make it possible for the students to become themselves."

Becoming oneself. Think about it. It isn't always easy.

How mindful and self-determined are your teachers, staff, and students? How mindful and self-determining are they becoming?

Sincerely,

Christine Mason

Center for Educational Improvement |

|

|